Delay Analysis | Knowing the unknown unknowns

Sean Hugo - Operations Director, Driver Trett Abu Dhabi examines the common practices and challenges of delay analysis on complex mega projects that are so prevalent in the Middle East.

Case background

Donald Rumsfeld, the then United States Secretary of Defence, gave notoriety to the saying that there are ‘known knowns’, ‘known unknowns’, and ‘unknown unknowns’ referring to matters pertaining to the Iraq war. In complex mega projects, the ‘unknown unknowns’ appear to be the rule rather than the exception; the result of this is that developing a robust baseline programme, that will stand the test of all scrutiny, is virtually impossible.

This was recently reconfirmed when Driver Trett were commissioned to undertake a strategic review of a contractor’s extension of time (EoT) claim on a prestigious project in the Middle East.

The project experienced significant overrun to the time for completion, besieged by iteration upon iteration of design changes to the original scope of works. The contractor was diligent (as far as reasonably practical) in submitting the contractually prescribed prospective time impact analyses (TIA), event by event. The contract administrator unequivocally rejected the TIA submissions.

The familiar failed path of planning

The original baseline programme quickly became obsolete. The impossible task of trying to effectively plan the ‘known unknowns’, and more particularly the ‘unknown unknowns’, was most likely the cause of the increasing speed with which the programme diverted from reality on site.

The original baseline programme, updated periodically with progress, became an unreliable forecasting tool as it did not reflect a reliable prospective critical path for the remaining works. The project followed the same sequence of events that befalls most of the complex projects we encounter in the region, it is a specific sequence; almost pathological. The original baseline programme, once approved, transitions into obsolescence upon periodic updating. This triggers the development of an acceleration programme to mitigate ‘contractor delays’ (largely due to the contract administrator’s rejection of the contractor’s numerous applications for an EoT). Finally, the proverbial ship can take on no more water and sinks - i.e. even the most optimistic contract administrator must concede that the completion date will not be met. Then follows a project wide reset with the development of unapproved target completion programmes.

All the while, during the implosion of the planning process, the contractor is left with little option but to continue with the submission of prospective TIAs in accordance with the contract specifications.

It was at this point that Driver Trett was approached to provide a viable strategy to take the contractor’s EoT claim forward and present this to the contract administrator in a fair, robust, and easily understandable format so that a negotiated settlement could be reached.

The perils of a prospective TIA

A prospective TIA was prescribed by the project specifications for quickly approximating the impact that an excusable delay event may have on the completion date (or another contract milestone).

The contract administrator handled this process by linking time and cost together; this is incorrect, a prospective time impact analysis is a mechanism for the contractor to seek an interim extension to the time for completion, where it has been prevented by the employer from discharging its obligations under the contract. It is also fully understood why contract administrators and employers adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach; awarding an EoT is definitely a precursor to a serious discussion about the associated costs. However, obstinately refusing to entertain awarding interim extensions of time to ‘protect’ the employer from incurring costs may be disingenuous and ultimately may prove the more expensive course of action.

It is not always a case of the contract administrator not administering the contract fairly, when it comes to awarding an EoT, but rather the inherent risks associated with assessing the impact of future events using, what many consider for reasons set out below, a highly dubious forecasting tool. The forecasting accuracy of a critical path method (CPM) network - a complex algorithm consisting of discrete tasks linked together to forecast a completion date - is reliant on many factors. The forecasting accuracy is not isolated to the quality of the programme at the baseline programme development stage. The forecasting accuracy is also distorted by less tangible external influences, such as contemporaneous decisions to mitigate and accelerate the works and changes to the future sequences of work, by choice or necessity.

Strategy and a way forward

The appropriate administration of the contract had clearly failed at this point but, most importantly, the contractor and the employer had not engaged in a formal dispute. The opportunity to negotiate a settlement still existed and presented the best outcome for both parties. Driver Trett proposed that, in the genuine interests of a fair negotiated settlement, a consolidated TIA should be carried out on a retrospective basis. This would consolidate and confine the analysis to events that, on the balance of probability, caused critical delay. Driver Trett recommended that a consolidated retrospective TIA should be carried out in accordance with the best practices set out in the AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 for Forensic Schedule Analysis (FSARP), i.e. an implementation of Modelled/Additive/Multiple Base (MIP 3.7)¹. Whilst this recommended practice did not form part of the contract, it provided rules of engagement for each party to agree to accept.

Before plunging straight into the mechanics of a MIP 3.7 implementation, it is imperative to highlight the complications faced when analysing delay on complex projects. As a result of the planning life cycle, the analyst is faced with several disconnected and conflicting sources of programme information. The specific programme to be used, and its current state, always become a matter of heated debate and, unless a degree of common sense prevails, hopes of a negotiated settlement will fade quickly.

Mechanics of a retrospective TIA

A retrospective TIA is essentially the same process as a prospective TIA, except that the analyst now has the benefit of hindsight (the project is completed or nearing completion). The prospective modelling of an event is now an actual fact and the event can be assessed in incremental periods of time otherwise known as "windows". It is defined in FSARP as follows:

“MIP 3.7 is a modelled technique since it relies on a simulation of a scenario based on a CPM model. The simulation consists of the insertion or addition of activities representing delays or changes into a network analysis model representing a plan to determine the hypothetical impact of those inserted activities to the network.”²

It is important to note that MIP 3.7 is a multiple base method. The term ‘base’ is simply terminology given to describe the date up to which the programme has been updated with actual progress. The multiple base method (MIP 3.7) ensures that the quantification of delay is confined to the period of analysis (or window). The analysis methodology can use updates of the original baseline, contemporaneous, modified contemporaneous, or recreated updates. Driver Trett selected to modify the progress updates of the baseline programme as it was felt that, with the benefit of hindsight, structural changes could be made to improve the forecasting accuracy. The practice of modifying updates is admittedly a minefield, with many differing opinions among delay experts and even triers-of-fact. Hallock and Mehta point out that: “in recent years, courts and arbiters have held that contract extensions should be based upon current schedules and not recreated schedules with the benefit of hindsight”³. This appears a blinkered view, if those changes align with the facts and retrospectively improve the forecasting accuracy.

There are several benefits to performing a retrospective TIA. Many of the assumptions made during the development of prospective mini-programmes (fragnets) to model the delay can now be converted to reflect the as-built status (fact). It can be ascertained in fact whether immediate successor activities, purportedly impacted during the prospective analysis, were in fact impacted.

What does a practical implementation look like?

Baseline validation

The first step in performing a retrospective TIA is to validate the baseline programme. This requires the settings of the software to be understood and documented, i.e. whether the network algorithm is calculated using retained logic, progress override, or actual dates. One of the most important steps is ensuring that the programme represents the full scope of work. In design-bid-build projects this is easier than design-build projects, where the scope of the project is initially poorly defined. Any aspects of the baseline programme that violate the contract provisions should be documented. There should be at least one continuous critical path from the inception of the project through to completion. Ideally this programme should not be updated with any progress.

Programme updates: validation, rectification and reconstruction

Due to the excessive manipulation of all the programmes during the planning life cycle, it was decided to start with a clean slate. The original baseline programme was used and updated periodically with progress only; no amendments were made to activity duration and interdependencies (logic) between activities. The baseline programme was updated in three-month intervals, for the duration of the project, to form revised progress updated programmes. Thereafter, each revised progress updated programme update was corrected to model fundamental changes to the work sequence, as could be determined retrospectively from the contemporaneous records.

Identification and quantification of delay events

There are two ways to analyse delay, it can either be quantified by ‘cause-effect’ or an ‘effect-cause’ approach. The ‘effect-cause’ approach relies on the observation of delay and then, once observed, it is up to the analyst to establish the cause of the delay through careful study of contemporaneous records. The observational methods follow this approach (as-planned versus as-built methodology). The cause-effect approach models specific events and tests the hypothetical effect by introducing the event, through the development of a fragnet into a progress updated programme at the time of the event. As it is a retrospective analysis, the causes are modelled with fragnets which are updated with actual start and finish dates to simulate an event which is a matter of fact. Additionally, a fragnet was developed for events which were clearly the liability of the contractor. This is an important step if the analysis is to be balanced and robust, but it is a step that contractors do not always carry out, preferring the ‘it’s all the employer’s fault’ approach.

An additive model schedule, with only employer caused delay events, is unsuitable for determining concurrent delay4, and thus entitlement to compensability. The development of both employer and contractor delay events is important to determine approximate concurrency. Concurrent delay is a complex matter, the interpretation of which hinges on provisions of the contract. (This is well beyond the scope of this article but further details regarding concurrent delay can be found in Karen Wenham’s article on page 10).

Determination and quantification of excusable, non-excusable and compensable delay

The final step is to assess excusable, compensable, and non-excusable delay, resulting from both contractor and employer events. This is achieved by separately impacting the contractor and employer caused events on the ‘unimpacted’, or host programme and comparing the results. Obviously, the interpretation of compensability hinges on how concurrent delay is defined in the contract.

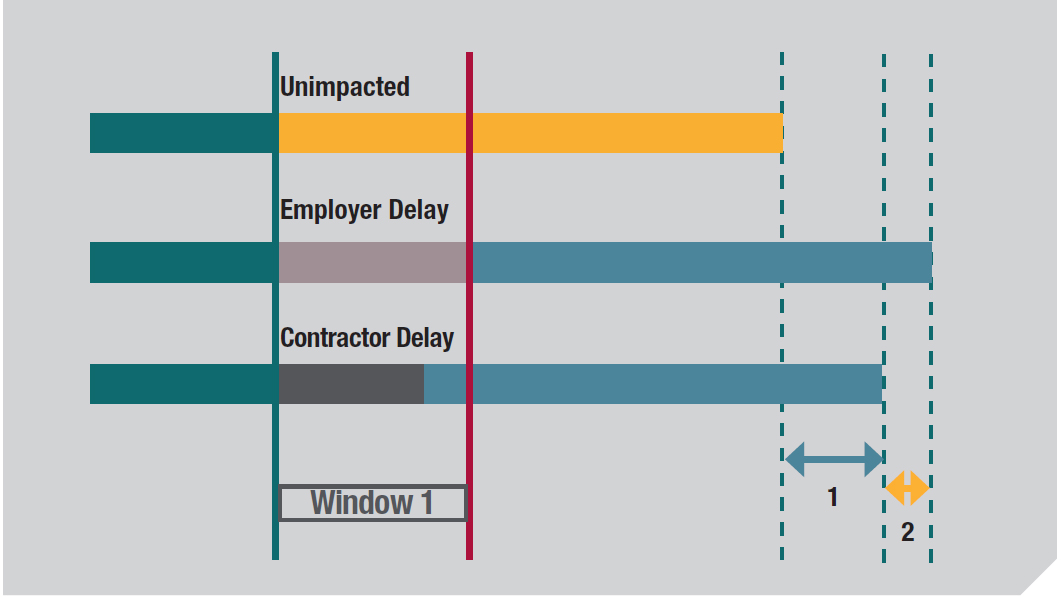

Figure 1 - Compensable & Excusable Delay

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of the unimpacted programme, the programme impacted with employer caused delay events, and the programme impacted with contractor caused delay events. It is a rare occurrence where a contractor records its own delay events, and this has to be retrospectively developed. This may be an area where a contract administrator can become more involved during the currency of the project as opposed to writing all encompassing ‘you’re in delay’ letters. The period of excusable delay exists where both the contractor and employer caused events to concurrently extend past the completion date (blue arrow labelled 1) and the period of compensable delay is the extent that the employer event pushes the completion date beyond the contractor caused event (orange arrow labelled 2). The employer caused event is driving the completion date.

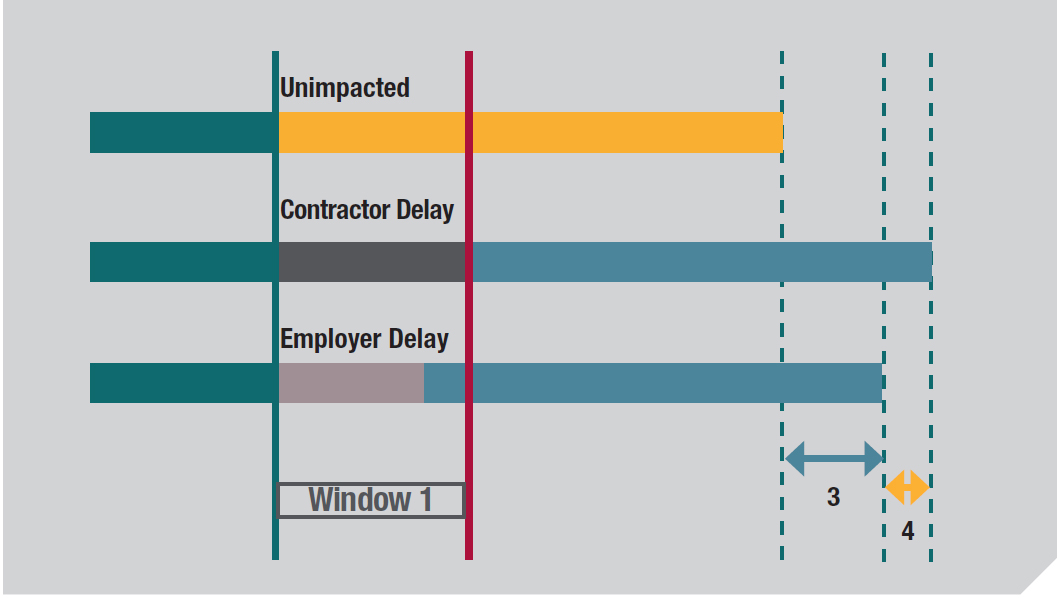

Figure 2 - Excusable and Non-Excusable Delay

Figure 2 illustrates the reverse condition where the contractor delay engulfs the employer delay and drives the completion date. This yields a result where a portion of the delay is excusable (blue arrow labelled 3) and a portion of the delay is non-excusable and non-compensable (orange arrow labelled 4). The contractor caused event is driving the completion date.

Lessons Learned

The most often cited criticism of a retrospective TIA is that the results do not reflect the facts. However, what it does provide is a mechanical, rules-based method with which both parties can agree to be bound by the method and results. If implemented correctly it will provide a fair approximation of project delay. There is no magic answer when it comes to delay analysis and there are a myriad of methodologies available to the analyst, which all have their own challenges to overcome. Perhaps it is time for the parties to agree to start agreeing on an appropriate methodology, or otherwise pay the price in a formal dispute setting. Stakeholders are warned that a blind reluctance to resolve complex issues may prove crippling to both parties if they blossom into costly disputes5.

¹AACE Internal Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 pg. 75/134

²AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 pg. 75

³BE Hallock and PM Mehta, ‘The Great Debate - TIA vs Windows; A Better Path for Retrospective Delay Analysis?’ [2007] N/a(CDR04) AACE International Transactions 1

4 AACE International Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 pg. 73/134

5 BE Hallock and PM Mehta, ‘The Great Debate - TIA vs Windows; A Better Path for Retrospective Delay Analysis?’ [2007] N/a(CDR04) AACE International Transactions 1