Stuart Holdsworth - Diales Technical Expert explores the development of tensile structures over the past twenty five years to provide shelter for events, and the operation of these structures, including causes of failures that have occurred and how such failures can be mitigated.

The rise in demand for tensile structures

It is the flexibility, adaptability, and affordability of tensile structures that makes them a desirable option for providing shelter at events, particularly events of a temporary nature. Over the past twenty-five years, tensile structures have become a standard feature of large gatherings requiring covered spaces, and have taken on increasingly substantial and sophisticated forms. Those older, regular attendees of the Glastonbury Festival, who can still remember the festival tents used prior to the 1990s, and compare those with the tents used today, can more readily appreciate this.

The original impetus for these large temporary structures was the development of ‘festival culture’ in the 1950s and 60s, cumulating in the arrival of events such as Glastonbury in the 1970s. In the 1980s, dance acts also began to use tents to provide weather protection for raves (Fig.1). The existing concept of the circus tent provided an acceptable venue, particularly as the dance acts did not require an audience facing proscenium stage. The traditional circus tent was adapted in size to suit this change of use, with the scaling-up of the tent being made possible by the transition from canvas to a plasticised material for the covering tent membrane. The form of these tents consisted of a circular footprint, with a single central king-pole, and a diameter of up to 44m.

This new generation of demountable covered venues also began to replace the traditional outdoor stages used at rock festivals. Unlike dance artists, rock groups required an audience facing proscenium stage and, coupled with a coincidental reduction in size of speaker stacks, this ultimately led to the evolution of the ‘festival tent’.

Fig. 1 - A modern circus tent, the central ‘cupola’ structure supports aerial performance above the ‘ring’

The festival tent

These large festival tents (with some covering areas of 1.5 to 2 hectares) evolved to fulfil a desire for covered space that included not only staging, but eventually also seating. The popularity of these larger tents was underpinned by the cheap and ready alternative that they offered to the hire of fixed venues.

The availability of new fabric materials, which were waterproof, retained strength, could be folded without damage, and could be fabricated simply, allowed new forms of tented structures to be created. The Kayam series of festival tents, which were developed in the 1990s and are still in use today, utilised these innovations and were the first forms of festival tents to have a different form of construction from previous concepts.

Fig. 2 - Kayam tent with ‘lifted catenaries’ at the right-hand side

The Kayam is large enough to hold a stage and allows theatre lighting rigs or other paraphernalia to be supported. It has several essential features that remain common to all tents of this type:

- The structure can be transported using standard flatbed lorries.

- It is quick to erect and dismantle (with no cranes being required).

- It is portable enough to be handled using simple construction equipment such as fork lifts and telehandlers.

The Kayam geometry and form is based upon the work of pioneers of tensile structures, particularly Frei Otto. Structurally, the Kayam features some novel characteristics, which makes the tent extremely flexible. The Kayam tent can, for example, be erected without prior installation of all of the side-poles, which allows easy access for the interior fit-out. This feature has resulted from the use of a catenary (scalloped) edge with discrete anchorage points (Fig.2). Openings of 15m width or greater can be achieved around the whole of the tent perimeter. Also, the number and arrangement of the Kayam tent masts are variable, allowing flexibility in the size of the structure for different events and locations.

Fig. 3 - Kayam tent in a triangular layout that allows a proscenium stage for rock music.

A variant of the Kayam tent features lifted catenaries (Fig.3), which allows the audience to stand outside the tent and look-in. By cutting back the catenary ends, and lifting these clear of the ground, the overall height of the entry points can be considerably increased.

A further development of the large tent system, the MT66 series, (Fig.4) followed on from the original Kayam series, removing the catenary edges that project beyond the side walls of Kayam tents altogether, thereby allowing a larger structure to be placed in a more constricted area. This change replicated the more traditional palisaded side pole anchorage systems used for the Big Top circus tents, and hence is known as a ‘palisade tent’. The tent form relies upon side poles to pull the fabric of the structure into shape.

Fig. 4 - MT66 series ‘palisade’ tent, note that the three in-line ‘king-poles’ precludes using this structure for anything other than dance/rave events

The flexibility provided by these new tent types, combined with the innovations that allowed them to take on increasingly substantial and sophisticated forms, also led to the extension of the traditional April to September hire season. Around the millennium, tensile structures became increasingly popular for winter events, such as ice shows and circus acts, operated by Feld Entertainment, Barnum & Bailey Circus, and Disney on Ice.

Safety considerations

Whilst the benefits of adopting large tensile structures to provide shelter at events are readily apparent, the success of these structures can only be made possible by a consideration of how they can be safely erected, operated, and dismantled. Important breakthroughs, such as improvements in the accuracy of weather forecasting, have assisted with this.

The design wind speed (the maximum wind speed that a structure is designed to withstand) is a critical consideration when evaluating the anticipated performance of the structure, as the predominant risk of failure for tensile structures is that they will be pulled out of the ground by gusts of wind.

The initial design of the Kayam tent was designed for use on sites with wind speeds of up to 35m/s, which was considered to be the minimum magnitude likely to be acceptable for the structure to be used widely throughout the UK. As with all innovation, these early festival tents soon attracted attention and copies were made. A significant production source of these copies were the continental circus tent manufacturers; artisans working in traditional ways, whilst adapting the tents to suit the new plasticised materials and structural forms. For the most part, continental designers resorted to designs based upon the principles used for frame and small circus tents, rather than the methods used for tensile structures developed from the work of Barnes in the UK, and Otto in Germany. The adoption of simpler calculation methods included the use of a lower design wind speed of 28 - 30m/s.

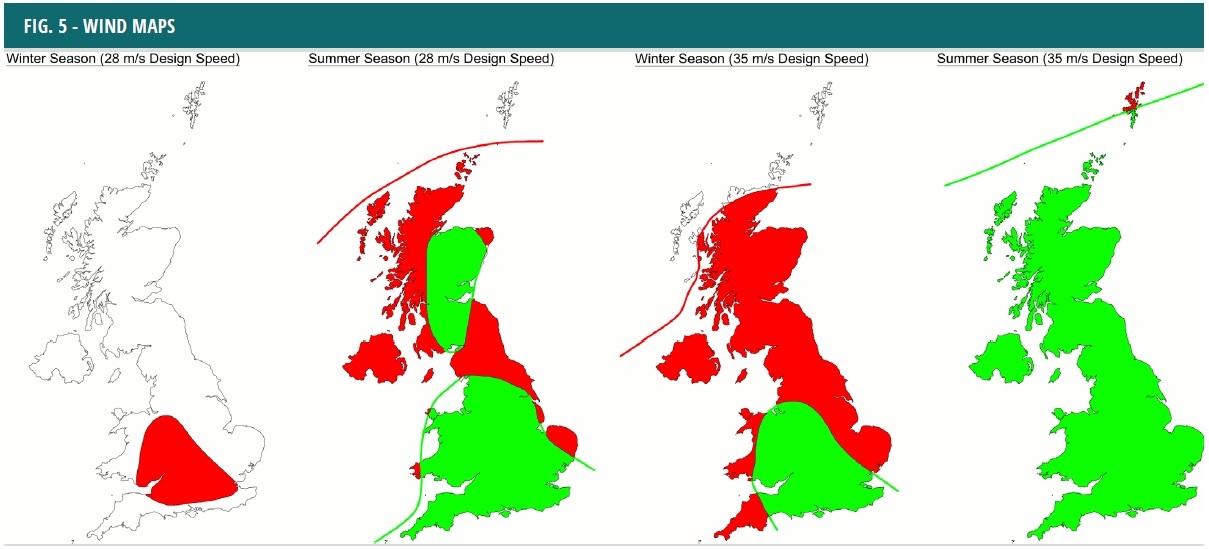

Using the principles expounded within the IStructE publication, ‘Temporary Demountable Structures’, as a basis for evaluating the suitability of a site on which to place a large tent, it can be seen that the design wind speed of the structure will dictate which regions of the UK are suitable locations for erecting the tent. To illustrate this, I have mapped out the suitability of UK locations (Fig.5) both summer and winter seasons, for tents designed for both 35m/s (the wind speed used as a basis for the design of the Kayam) and for 28 m/s (the standard wind speed used for the design of frame tents). It is clear that adopting a lower design wind speed severely limits the location and season in which these structures can be used.

More recently, since the extension of the traditional hire season around the millennium (which removed the safeguard of traditional circuses and funfairs retiring to winter quarters that prevented exposure of the tents to the worst of the winter’s weather), higher design wind speeds have been adopted to allow the tents to be more widely used during these winter months. The Tensile 1 (now Valhalla) tent, has for example, been designed to a wind speed of 50m/s, which has also allowed it to be used internationally.

Despite the guidance given within the IStructE publication, in reality few of the tent suppliers undertake a review using these methods, and instead rely upon weather forecasting and previous knowledge of the sites. In the event of high forecasted winds, the tents are taken out of use and various safeguarding measures, such as double staking, are taken to protect the structure. However, in reality failures do happen, and injuries have resulted from some of these failures. Fortunately, most have occurred when the tent has been taken out of use, or during the build-up or breakdown phases, and, to date, a festival tent failure has not resulted in a serious disaster whilst in public use. The risk of failure should nevertheless be mitigated as far as possible, to prevent any injuries or damage to property. I will discuss the causes of failures that have occurred and precautions that ought to be taken to prevent such failures in a future Digest.